Dr Sunetra Mondal explains Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Related Disorders and how best to manage them.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common endocrinopathies affecting women across their reproductive life-span, and the most common cause of menstrual irregularity and infertility in women. Diagnosis often peaks during the peri-pubertal, peri-partum and even peri- menopausal ages. The condition varies throughout a woman’s life: during adolescence, diagnosis is challenging since irregular periods and acne may be part of normal puberty; during reproductive age, infertility and metabolic risks become prominent; and around menopause, metabolic complications may persist or worsen, even if ovarian androgen production declines.

Pathophysiology

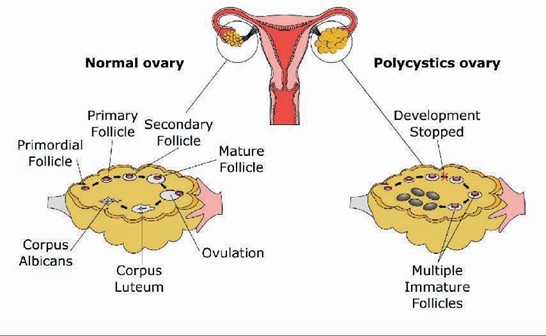

It chiefly involves a trio of key pathophysiological abnormalities: hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction, and polycystic ovarian morphology. These components form the cornerstone of PCOS diagnosis and understanding. However, the pathogenesis of PCOS is much more complex and multifaceted involving multiple hormonal dysregulation; and players at the level of the hypothalamus, ovary, liver, adipose tissue and adrenals.

PCOS pathophysiology involves a complex interplay of hormonal and metabolic disturbances. Insulin resistance is central, leading to higher circulating insulin levels that stimulate ovarian theca cells to produce excess androgens. This hyperinsulinemia also reduces hepatic production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), increasing free testosterone, which contributes to clinical hyperandrogenism.

Elevated luteinizing hormone (LH) relative to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) further drives androgen production by the ovaries. Leptin, an adipose-derived hormone involved in energy regulation, may influence hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis dysfunction, worsening menstrual irregularities.

Additionally, excess estrogen without the balancing effect of progesterone due to anovulation leads to endometrial thickening and irregular bleeding. Together, these disruptions create the hormonal environment characteristic of PCOS, underlining both reproductive and metabolic abnormalities.

Clinical manifestations

Hyperandrogenism refers to elevated levels of male hormones, such as testosterone, which lead to clinical signs like excessive facial and body hair (hirsutism), inflammatory acne, and sometimes male-pattern baldness.

This occurs due to enhanced secretion of androgen production from the hyperplastic ovarian stroma. While there are objective scores like the modified Ferriman Galleway score for hirsutism, or Ludwig scale for alopecia, it is mainly the degree to which the patient is bothered that merits importance.

Ovulatory dysfunction means irregular or absent ovulation, which results in irregular menstrual cycles or amenorrhea and often contributes to infertility. By definition, oligomenorrhoea refers to an inter- menstrual interval exceeding 35 days during the reproductive years and 45 days during adolescence; while polymenorrhoea refers to a cycle interval shorter than 20 days.

Polycystic ovarian morphology, detected by ultrasound, shows enlarged ovaries with multiple small (29 mm) follicles arranged peripherally, sometimes described as a “string of pearls.” However, this ultrasound finding alone is not diagnostic unless accompanied by clinical or biochemical abnormalities.

Diagnostic criteriae

Several different diagnostic criteriae have been developed for PCOS including those given by the NIH in 1990, the most commonly accepted Rotterdam criteria and the Androgen-Excess Society criteria. The Rotterdam criteria, established in 2003, remain the most widely accepted diagnostic framework and is recommended by most global guidelines today. They require the presence of any two of the following three features:

- Clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism

- Oligo- or anovulation

- Polycystic ovaries on ultrasound, after excluding other disorders that mimic

This approach acknowledges the heterogeneity of PCOS, where some women may have hyperandrogenism and irregular periods but normal ovarian morphology, while others might have classic polycystic ovaries but regular ovulation. It is important to rule out the secondary causes of PCOS before a diagnosis is made. (Table 1)

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for PCOS

| NIH 1990 | Rotterdam criteria 2003 | AES 2006 |

| Menstrual irregularity and Hyperandrogenism | At least 2 out of 3:

1. Chronic oligo-anovulation 2. Hyperandrogenism 3. Polycystic ovarian morphology |

Hyperandrogenism and

at least 1 out of 2: 1. Chronic oligo-anovulation 2. Polycystic ovarian morphology |

| Exclude Secondary Causes: thyroid dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia, NCCAH, adrenal or

ovarian tumors, Cushings syndrome or acromegaly |

||

Abbreviations used : NIH = National Institute of Health ; AES = Androgen excess society ;

NCCAH = Non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Endocrine mimickers and secondary causes of PCOS

Because PCOS shares features with several other medical conditions, it is critical to distinguish it from mimickers and causes of secondary hyperandrogenism. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), primarily due to 21-hydroxylase enzyme deficiency, is a genetic disorder causing excess adrenal androgens and can present with similar symptoms, including hirsutism and menstrual irregularities. Unlike typical PCOS, CAH often shows elevated 17- hydroxyprogesterone levels and may manifest in childhood or adolescence. The patients are often non-obese, may have a family history and more severe features of hyperandrogenism like clitoromegaly.

Adrenal or ovarian tumors are rare but serious causes, may secrete large amounts of androgens, leading to rapid-onset and severe virilization symptoms such as deepening of voice, clitoromegaly, or sudden menstrual cessation.

Hyperprolactinemia, caused by pituitary adenomas or more commonly secondary to medications, disrupts gonadotropin

secretion leading to menstrual irregularities and sometimes mild androgen excess.

Thyroid disorders can occasionally mimic PCOS by affecting menstrual cycles and metabolism. Proper identification of these conditions ensures accurate treatment and prevents unnecessary interventions.

Metabolic comorbidities and complications of PCOS

Metabolic comorbidities are commonly associated with PCOS and often contribute substantially to morbidity. Obesity is highly prevalent and worsens insulin resistance, exacerbating both reproductive and metabolic symptoms. Approximately 40 to 70 per cent of women with PCOS are overweight or obese, which increases cardiovascular risk. Insulin resistance itself is a central feature of PCOS, affecting both obese and non-obese women, and predisposes to impaired glucose tolerance and Type 2 Diabetes mellitus at an earlier age compared to non-PCOS populations.

Hypertension is also more common in PCOS, consistent with increased cardiovascular risk profiles. Another important metabolic complication is metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD, formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease (NAFLD or MASLD), where excess fat accumulates in the liver due to insulin resistance, increasing risk for progressive liver disease like fibrosis and cirrhosis or rarely hepatocellular cancers.

Table 2. Battery of hormonal and metabolic investigations recommended in PCOS with interpretation and caveats

| Investigations | Interpretation and caveats |

| Total Testosterone | To be measured if clinical signs of hyperandrogenism are unclear or absent. Total Testosterone (t) by LC -MS/MS

Free testosterone Calculated or by equilibrium dialysis, or ammonium sulfate precipitation methods are recommended

Direct free testosterone assays (RIA/ECLIA) are not recommended

To be measured during Day 2 to Day 5 of menstrual cycles or at any time if suspected anovulatory cycles

No clear cut-offs but usually total testosterone >55 ng/dL (1.91 nmol/L) or free testosterone >9 pg/ml or FAI > 4.5 usually accepted

No role of repeated androgen testing for monitoring

Very high T (>200 ng/dl or 2-fold ULN) – suspicion for androgen-producing tumours, ovarian hyperthecosis |

| Prolactin, TSH | To rule out hyperprolactinemia and hypothyroidism a secondary cause for PCOS

Mild increase in prolactin is expected in PCOS |

| DHEAS | To be done in cases with severe clinical hyperandrogenism

DHEAS – > 700 ug/dl – suspect adrenal tumors. |

| 17OHprogeste

rone (Follicular phase) |

Basal or stimulated 17OHP > 2 ng/ml – NCCAH. |

| LH,FSH | Not routinely recommended; Supportive evidence in non-obese PCOS ; no

definite clear cut-off |

| AMH | Not routinely recommended; supportive evidence ; correlates well with pCO

morphology ; most sensitive in classic, anovulatory PCOS |

| FPG, PP-OGTT

Lipid profile OSA screening |

All women with PCOS |

| Insulin assays;

HOMA-IR |

Not recommended at baseline or at follow-up |

Abbreviations used : LC-MS/MS : Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry ; RIA = Radioimmunoassay, ECLIA = Electro chemiluminescence assay ; TSH = Thyroid Stimulating Hormone; DHEAS = Dehydro epiandrosterone; LH = Luteinising hormone; FSH = Follicle Stimulating hormone;

AMH = Anti Mullerian hormone; FPG = Fasting Plasma Glucose ; PP = Post prandial ; OGTT = Oral glucose tolerance test ; OSA = Obstructive sleep apnea; HOMA-IR = Homeostatic model assessment

insulin resistance ; NCCAH = non -classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Sleep apnoea, particularly obstructive sleep apnoea, is frequently observed in PCOS, linked to obesity and hormonal disturbances; it significantly impacts cardiovascular health and quality of life.

Notably, lean women with PCOS those who have a normal body mass index also show marked insulin resistance and increased risk for metabolic abnormalities, underscoring the importance of screening metabolic health irrespective of weight.

PCOS in special populations

Adolescence

PCOS manifests differently across the lifespan and special populations therefore require unique management strategies.

Adolescents often face diagnostic confusion because features like irregular menses and acne can be physiological during puberty. Similarly, polycystic ovaries are common in adolescents. Irregular menstrual cycles are normal in the first-year post menarche and it’s normal for intermenstrual interval to be increased to 45 days in the first 3 years after menarche.

However, intermenstrual interval of < 21 or

> 45 days in the first three years post menarche or > 90 days after 1 year post menarche or primary amenorrhoea by age 15- or 3-years post thelarche are abnormal and need evaluation.

Early recognition of adolescents with PCOS or “at risk” for PCO is essential to manage symptoms and prevent long-term consequences such as Type 2 Diabetes, dyslipidaemia, and infertility. In adolescence, treatment prioritizes normalization of menstrual cycles,

addressing hirsutism/acne, and metabolic risk reduction, often starting with lifestyle changes before medication.

Menopause

During menopause and perimenopause, although ovulation ceases, the history of hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance may carry ongoing risks including cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis. Postmenopausal women with prior PCOS should be monitored carefully for metabolic syndrome components, and treatment should focus on reducing cardiometabolic risks.

Management of PCOS recent advances

Treatment of PCOS is multifaceted and must be individualized, generally including lifestyle measures such as dietary changes

and exercise to reduce insulin resistance, pharmacological therapies to address hormonal imbalances (like combined oral contraceptives or anti-androgens), and fertility treatments when pregnancy is desired.

Combined estrogen + progesterone combined pills are the recommended first line and should be used in all PCOS with anovulation

+/- hyperandrogenism while metformin may be used as first line for overweight/obese PCOS, especially with dysglycemia. There is also a role for monthly progesterone withdrawal bleeding for those with only oligomenorrhoea without hyperandrogenism or dysmetabolic features.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), commonly

used in Type 2 Diabetes and obesity, improve insulin sensitivity, reduce appetite, promote significant weight loss, and have demonstrated reductions in androgen levels and improvements in menstrual regularity in PCOS. These agents may address core metabolic defects and have emerging roles in PCOS management especially in obese patients. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), another class of antidiabetic drugs, have shown potential benefits in improving glycaemic control, promoting weight loss, and reducing cardiovascular risk factors in PCOS populations, although more extensive clinical trials are needed. These newer therapies could complement established treatment modalities, potentially offering better outcomes in resistant or metabolically challenging cases.

PCOS is a multifaceted syndrome

and exercise to reduce insulin resistance, pharmacological therapies to address hormonal imbalances (like combined oral contraceptives or anti-androgens), and fertility treatments when pregnancy is desired.

Combined estrogen + progesterone combined pills are the recommended first line and should be used in all PCOS with anovulation

+/- hyperandrogenism while metformin may be used as first line for overweight/obese PCOS, especially with dysglycemia. There is also a role for monthly progesterone withdrawal bleeding for those with only oligomenorrhoea without hyperandrogenism or dysmetabolic features.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), commonly

used in Type 2 Diabetes and obesity, improve insulin sensitivity, reduce appetite, promote significant weight loss, and have demonstrated reductions in androgen levels and improvements in menstrual regularity in PCOS. These agents may address core metabolic defects and have emerging roles in PCOS management especially in obese patients. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), another class of antidiabetic drugs, have shown potential benefits in improving glycaemic control, promoting weight loss, and reducing cardiovascular risk factors in PCOS populations, although more extensive clinical trials are needed. These newer therapies could complement established treatment modalities, potentially offering better outcomes in resistant or metabolically challenging cases.

PCOS is a multifaceted syndrome encompassing reproductive, endocrine, and metabolic disturbances. Its clinical spectrum is broad and varies with age and individual characteristics. The central pathophysiologic triad of hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction, and polycystic ovarian morphology defines the condition, but diverse phenotypes necessitate thorough clinical evaluation and exclusion of mimicking disorders. Metabolic comorbidities such as obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertension, MASLD, and sleep apnoea complicate health outcomes and demand vigilant screening and comprehensive management.

Special attention to adolescents and menopausal women ensures appropriate life-stage-specific care. Emerging treatments that target metabolic dysfunction offer hope for improved management. Overall, an endocrinologist’s role is pivotal as they integrate hormonal and metabolic therapies aiming to address the root causes of PCOS, improve symptoms, and reduce long-term health risks, guiding women towards better quality of life and holistic health.

Dr Sunetra Mondal is the Assistant Professor, Dept of Endocrinology, NRS Medical College in Kolkata